Lacan, Kohut, and the Real You

Vladimir Nemet

“The Other is not what we encounter; it is the place from which the subject speaks, the locus of the signifier that structures desire.”

— Jacques Lacan, Écrits (1966)

1. Introduction: Theory and Immediate Encounter

Every psychological theory, whether contemporary or traditional, at its core speaks to the relationship of I and Thou — even if it rarely recognizes it. Its models, concepts, and classifications attempt to explain human behavior, patterns, and emotions, yet what is truly crucial — the immediate encounter with the Other — always remains hidden, beyond the reach of theoretical constructs. In short: the Other cannot be directly touched, at least according to theory.

This holds true even for Lacan, whose theory of the unconscious structured like language demonstrates that the subject cannot exist without the Other. But where is this Other? For Lacan, the Other is present through the symbolic and the imaginary — through words, signifiers, and norms — yet never in direct encounter. Whether we speak of the small or the big Other, the imaginary or the symbolic, the Other remains mediated and elusive; direct contact is simply impossible.

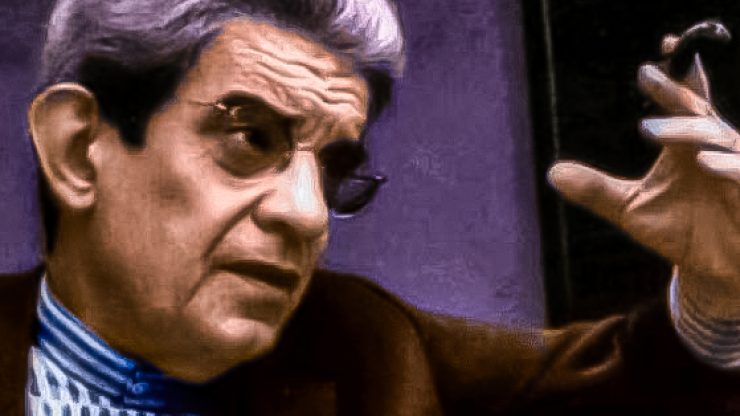

Jacques Lacan redefined psychoanalysis when he asserted that the unconscious is structured like language. This idea shifted the focus of psychoanalysis from inner contents to the very structure of speech. Yet within this revolutionary conception lies a limitation: if the unconscious is language, who is speaking? And to whom is it addressed? In Lacan’s theory, as in many modern interpretations of the subject, what Martin Buber calls Thou disappears. The Real becomes ‘impossible,’ and the I–Thou relationship vanishes within the web of signifiers.

This article seeks to restore Thou to the center of psychoanalysis — to show that the Real is precisely the moment of direct I–Thou relationship, when the symbolic and imaginary give way, leaving only presence.

2. The Key to Lacan

Lacan is often admired in academic circles for his hermetic style. His philosophical and structured approach conveys an impression of complexity and exclusivity, yet in the real encounter with human subjectivity, his theory becomes surprisingly simple. Viewed through the lens of the I–Thou relationship, the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real are no longer abstract categories but direct descriptions of encounters with the Other.

Academic structures themselves are often hermetic; studying theories and signifiers without deep clinical experience easily loses touch with human reality. That is why Lacan can appear difficult and inaccessible — his power remains hidden to those who have not felt the dynamics of real encounters. Yet when the perspective shifts to the phenomenological, experiential I–Thou encounter, Lacan ceases to be abstract and becomes a theory of living meeting, of the real Other, directly applicable in therapy. In other words, the I–Thou relationship becomes the key to reading Lacan, as well as other psychological theories.

3. Three Registers: Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real

Lacan can be understood simply through the I–Thou relationship, in which Thou is always the Other — small or large, depending on the register. His three registers — Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real — can be read in parallel with Kohut’s triads: ambitions, ideals, and twinship.

The Imaginary is the space of narcissistic identification, of images and reflections, where Thou functions as the small Other (le petit Autre), a mirrored figure through which the ego recognizes and affirms itself. In that moment, the subject unconsciously says: “I am perfect, and you are part of me.” The Other becomes an extension of the grandiose self, creating a sense of wholeness and power, but also the tension of rivalry, while the Imaginary preserves the narcissistic illusion of unity.

The Symbolic, on the other hand, introduces the experience of the big Other (le grand Autre) — language, law, and ideals. Here, Thou is experienced as a source of meaning and authority, corresponding to Kohut’s ideals, when the subject says: “You are perfect, and I am part of you.” The Other now provides direction, structure, and a moral compass, enabling orientation and meaning, while simultaneously shattering the illusion of the ego’s grandiosity, for the Other is no longer a mirror but a present figure that structures reality.

For Lacan, the Real is not the encounter with a living, actual Other; it designates that which always escapes the symbolic and imaginary structures, the void, the gap in meaning, the place where ego and law cannot fully grasp subjective experience. The Real is trauma, the impossibility of fully capturing the Other, the aspect of relationship that remains unspoken and unassimilated, where the real Thou remains inaccessible and elusive.

4. Lacan and Kohut

Heinz Kohut, in contrast, sees the Real through the lens of twinship as an encounter with the present Other, a space in which the ego can genuinely connect with another without projections or idealizations. Kohut defines twinship as the experience of being human among other humans. In this framework, the Real becomes the experience of presence, the foundation of wholeness and authentic relationship, and it is precisely through this encounter that the dynamics described by the theory of parallel identities unfold: the capacity for I and Thou to exist simultaneously in a continuous exchange of perspectives, without loss of ego integrity or the illusion of a grandiose self.

Psychoanalytic theories do not arise in a vacuum; they are always products of the personal context, experiences, and professional framework of their authors. On this basis, I believe Lacan did not have the experience of immediate presence of the Other in a clinical sense, which explains why the presence of a living, real Other has no place in his theory. His thought develops through language, structures, and signifiers, not through phenomenological encounter, reflecting his intellectual and academic context, where clinical experience was not the primary source of insight.

5. The Real as Direct I–Thou Relation

What is the Real?

From a phenomenological perspective, the Real is not that which escapes; it is that which is. It is the moment of immediate reciprocity, when projections, ideals, and meanings fall away, leaving only presence. The Real is not trauma, but the truth of the relationship. The Real is more than an abstract register; it is material evidence of Otherness.

At that moment, there is neither small nor big Other — there is only Thou. How is this possible? According to the theory of parallel identities, we are always already the Other — Thou is present even when the subject has not yet recognized it, even when the ego seeks confirmation in the mirror or in the rules of the symbolic world. The Real is the awareness that the Other has always been a part of me, inseparable from my I, yet present as a distinct, authentic presence. It testifies that the encounter with the Other is not a potential, a future possibility, or a fantasy, but a fundamental structure of our subjectivity, present in every moment, in every interaction, independent of our projections, ideals, or grandiose selves. The Real is a silent sign that Otherness always exists, surpasses us, and points beyond, present and real.

Immediate Encounter

This shift changes the entire psychoanalytic perspective: rather than the goal being the deconstruction of signifiers, the goal becomes immediate encounter. Instead of the analyst functioning as a voice of language, the analyst appears as Thou, witnessing the client’s reality through relationship, not interpretation. In this sense, the Real is not what is missing, but what already exists — and must only be grasped.

The Real is not what cannot be spoken, but what does not need to be spoken to exist. In this sense, the psychoanalysis of the future cannot be the analysis of language, but the analysis of presence — the encounter in which I and Thou exist for each other, without mediation.

Here begins a new spirituality of psychoanalysis: the return of the real Thou, that which has always been here, but remained unspoken.

Conclusion

A phenomenological approach restores Thou to the center of psychoanalysis. The Real is not an abstract void, but the presence of the Other that has always already been here, inseparable from our I. Lacan’s theory, through the Imaginary and the Symbolic, shows the structures through which the subject acts, while Kohut’s twinship experience opens space for true encounter.

By combining these perspectives, through the lens of parallel identities, psychoanalysis becomes a theory of living relationship, where I and Thou coexist, exchange, and affirm each other — creating an authentic, present, and indelible structure of subjectivity.

Literature

Husserl, E. (1913). Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. London: Routledge.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time. New York: Harper & Row.

Levinas, E. (1961). Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Buber, M. (1923). I and Thou. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lacan, J. (1966). Écrits: A Selection. Translated by A. Sheridan. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Kohut, H. (1977). The Restoration of the Self. New York: International Universities Press.

Vladimir Nemet (2025). New Psychoanalysis and Parallel Identities. https://www.academia.edu/129607071/NEW_PSYCHOANALYSIS_AND_PARALLEL_IDENTITIES