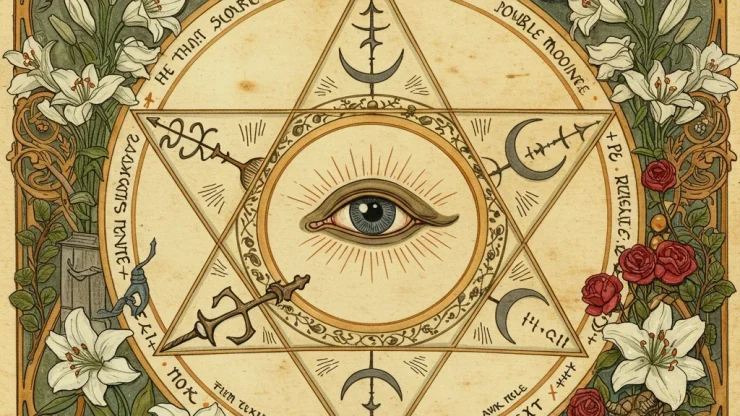

The Other as the All-Seeing Eye

Vladimir Nemet

“The artist is torn between the need to hide and the need to show himself.”

– Donald W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality

“It is a pleasure to hide, but a tragedy if one is not found.”

– Donald W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality

Introduction

Why is the experience of the Other often mysterious, almost unattainable? Why is it difficult to see another person as a living presence, as a subject with an independent perspective? Every encounter with the Other, no matter how ordinary, carries a complex dynamic of perception, empathy, and introspective mirroring. It seems that there is a wall, thin or thick, often invisible yet deeply present, between us and the Other.

This article aims to illuminate the fundamental problem of experiencing Otherness – the invisible wall that forms between us and the Other. We know that the Other is essential for our psychic cohesion: they structure us, regulate the rhythm of our affects, and confirm our subjectivity. Without their reflection, without their gaze and emotional response, it is difficult to be sure we are truly alive, present in our own psychic world.

Yet paradoxically, the Other often remains hidden or unavailable to our experience. The core thesis of this article is that when we try to hide ourselves from the gaze of the Other, the Other disappears from our horizon, depriving us of the possibility of experiencing a real, living encounter. Through the theory of parallel identities, Winnicott’s ideas about the artist, affect phenomenology, and the concept of thymos, I aim to show that the solution lies not in withdrawal, but in courageously revealing ourselves to the Other.

The Mystery of the Other

The experience of the Other carries an inherent, almost magical elusiveness. No matter how much we try, they always appear partly absent or out of reach. This is not merely a phenomenon of interpersonal experience; the wall toward the Other often arises within our own psyche. This wall can be imagined as a two-way window: a channel that allows affects, thoughts, and impulses to flow from us to the Other and from the Other to us.

When we want to hide parts of ourselves – destructive thoughts, impulses, or fantasies we consider unacceptable – we close this window. Paradoxically, this act of hiding not only protects us from potential judgment, but also prevents us from experiencing the Other. The Other disappears from our psychic horizon because the channel of communication ceases to function. The wall becomes doubly restrictive: it protects our privacy, but simultaneously prevents encounter and reflection.

From a phenomenological perspective, this wall emerges from a combination of fear, shame, and the internal tension between the desire to be seen and the need to preserve intimate parts of ourselves. The two-way window makes the experience of the Other possible – but only if it remains open.

The Other as the Foundation of Our Being

The Other is not merely an external observer; they are the ontological condition of our subjective existence. Their gaze structures and affirms us. When the Other reacts to us, they affirm not only what we display, but also our capacity to be seen. Without this reflection, the sense of our own vitality becomes uncertain.

The two-way window plays a central role here: the channel toward the Other allows simultaneous visibility and exchange of affects. When we close it to hide parts of ourselves, we interrupt the flow of communication and reflection. By hiding, we not only protect our vulnerability but also unconsciously remove the Other from our experience – they cease to exist as a living presence because they no longer have access to our affects, and our affects no longer reflect their presence.

This paradox illustrates the necessity of courage in opening the two-way connection: only through an open window can we truly experience the Other, affirm our identity, and allow affects to gain existence. Hiding creates an illusion of safety but leads to isolation and fragmentation of inner life.

Parallel Identities and the All-Seeing Eye

According to the theory of parallel identities, the Other is always already present within us. They are not merely an external entity entering our life, but a figure of Otherness inscribed in our psychic structure from the beginning. This inner observer knows and sees what we often refuse to acknowledge, making them akin to an all-seeing eye.

This “all-seeing eye” is not a threat but a potential: their gaze allows introspective recognition of affects, affirms subjectivity, and enables the integration of experiences we would otherwise hide. By opening the two-way window toward the Other, we allow affects to flow, reflect, and metabolize. Revealing ourselves to the Other becomes a means for this relationship to become real and alive without losing our integrity.

The two-way window pulses with our affects, breathes with the presence of the Other, and enables continuous reflection. Every affect, including anger, fear, or envy, gains existence only when reflected through this channel. When the window is closed, affects are suppressed and become unconscious, and the Other disappears as a living presence.

Winnicott – The Paradox of Hiding and Revealing

Donald Winnicott describes the artist – and, by extension, every human – as torn between the need to hide and the need to show. Hiding preserves the vulnerable parts of the self, while revealing opens the space for encounter. This tension is not a problem to solve; it is an ontological condition of our subjectivity.

Winnicott also emphasizes that the pleasure of hiding is natural and psychologically important: we wish to protect the inner core of ourselves as precious and safeguarded. Yet tragedy arises if one is not found – if no one sees our presence, affects remain unrecognized, vitality is lost, and the psychic channel to the Other remains closed. Depression, lethargy, melancholia appears.

The true self appears only in a space where there is enough safety to be seen, but not scrutinized. Through this paradox, the Other ceases to be a threatening, all-seeing eye and becomes a living presence, a subject with whom we can share affects and experience. Creative energy and introspective strength emerge through the constant alternation of opening and closing the window, through the dynamic presence of affects and reflection of the Other.

Thymos – The Original Form of Anger and Vitality

In discussing anger and affects, it is essential to consider thymos, a concept from Greek philosophy that designates the original form of vital anger and life energy. According to Plato and other classical authors, thymos is the inner drive for dignity, recognition, and the ability to defend one’s own value. It is an energy that makes us simultaneously vulnerable and powerful: it gives us the strength to respond to injustice, affirms our identity, and defends the boundaries of the self.

Interestingly, for the past two thousand years, thymos has often been regarded as a negative energy to be controlled or eliminated. In philosophical and moral tradition, anger and strong affects were considered a threat to social order and inner balance. Plato, for instance, associates thymos with impulsive anger that must be disciplined by reason and virtue. Later moral and religious traditions often treat anger as a dangerous force best suppressed or transformed.

From a phenomenological and psychoanalytic perspective, thymos can be understood as a vital form of anger that is not inherently destructive but a vital energy that drives affects outward and enables contact with the Other. When this impulse is repressed or hidden, the connection to inner strength is lost, and affects become fragmented and unconscious. Opening the two-way window toward the Other allows thymos to be metabolized – it becomes energy that not only affirms our boundaries and identity but also enables a real encounter with the Other.

In the context of Winnicott’s paradox of hiding and revealing, thymos explains why showing ourselves to the Other is not merely courageous but ontologically necessary: it is the energy that makes us visible, present, and psychologically whole. By hiding, thymos does not disappear, but becomes invisible, unintegrated, and loses its vital function.

Conclusion

Experiencing the Other is paradoxical and requires courage: the Other is always present, sees and knows, but true experience arises only when we open the window toward them. Hiding does not solve the problem – it deepens isolation and blocks affective reflection.

The solution is not withdrawal, but revealing ourselves to the world and to the Other. An open window allows our affects to be metabolized, enables the Other to become a living presence, and allows our subjectivity to remain whole and vital. Winnicott’s artist within all of us lives through the tension of hiding and revealing; it is from this tension that authentic encounter is born, rich with affects and the reality of the Other.

Affects that are not reflected to the Other do not exist phenomenologically; revealing ourselves allows them to gain existence and integration. Thymos, as the original vital anger, provides the energy for this act, affirms our identity, and enables a real encounter. Only in this space is it possible to truly experience the Other, feel their presence, and develop the ability to be seen and alive before the Other.

Literature:

- Buber, M. (1970). I and Thou (R. G. Smith, Trans.). Charles Scribner’s Sons. (Original work published 1923)

- Kohut, H. (1984). How Does Analysis Cure? University of Chicago Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1945)

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and Reality. Tavistock Publications.

- Vladimir Nemet (2025). New Psychoanalysis and Parallel Identities , Embodiment and parallel identities