How does analysis cure?

Vladimir Nemet

“The patient’s progress depends less on the clever interpretation than on the real human contact that confirms his existence and worth.”

Sándor Ferenczi, Confusion of the Tongues Between the Adults and the Child,1949.

Introduction

All psychological problems we know are born in the shadow of invisibility—from the feeling that our thoughts, emotions, and existence go unnoticed, as if the world does not see our presence. Problems only recede when someone sees our existence, recognizes it, and gently accepts it. It is precisely this light of recognition, warm and reassuring, that we can sense in the short story of the boy Charlie by psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut:

The Boy Charlie and the Pigeons

Charlie had just begun to walk. Until then, he had spent most of his time in his mother’s arms, feeling the security and warmth he so desperately needed. That day, they were sitting in the park. The sun gently illuminated the lawn, and a light breeze carried the scent of fresh earth and the chirping of birds.

Suddenly, Charlie saw some pigeons. His eyes widened with curiosity and excitement. For the first time, he felt an impulse to separate from his mother’s safety and approach them. Slowly, he lifted his feet and began to move forward, taking small, uncertain steps.

Halfway there, as the pigeon was still a little ahead, his heart raced. Fear arose—the world suddenly seemed bigger and unfamiliar. Danger was present!

Charlie looked at his mother with fear – is everything okay?

Everything was okay! His mother’s presence had not disappeared; she was there, like an invisible safety net. In that small moment, Charlie took his first real step toward the world outside his mother’s arms, knowing he could always return if needed.

1. Growing Up

In this short story, Kohut tells us: security is not in merging, but in the gaze that sees you, in the hand that guides you, in the heart that understands you. A mother’s pride, like a mirror, reflects Charlie’s strength and courage, while empathy creates an invisible net that gently supports every fall and every step he takes.

Charlie’s story reveals the full cycle of growing up—from initial fusion, through necessary separation, to returning to the mother through empathy. Everyone must go through these three experiences to feel their own wholeness, vitality, and sense of existence.

Yet the story speaks of something more. It reflects the path of every client in contemporary Kohutian psychoanalysis. A client entering therapy often carries the sense that something is wrong—that life is passing them by, that they have lost the sense of fullness and vitality they once had. Feelings of emptiness and loss are accompanied by symptoms: anxiety, depression, addictions, and countless other ways the soul tries to maintain its integrity.

On the surface, the client may desire only the disappearance of symptoms. But beneath this lies a deeper yearning—to feel connection again, to be seen and experienced.

This is the purpose of psychoanalysis. But which kind of psychoanalysis?

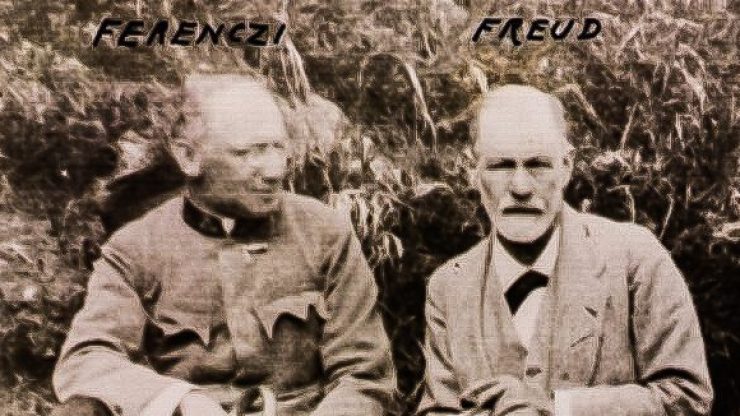

2. Freud, Ferenczi, Kohut

Freud believed in the power of words. In his vision, the analyst is the one who knows—a decipherer of the unconscious, a priest of the logos who liberates truth. Words separate; they enter like a scalpel, revealing hidden layers of meaning and thus healing. Yet the act of interpretation can become a new form of alienation—the person, illuminated by insight, may feel even more alone.

Sándor Ferenczi was the first to doubt Freud’s idea of neutrality. He saw that in therapy there is not a transfer of information, but mutual vulnerability. The analyst cannot hide behind theory—body and voice speak before words. Empathy becomes truth, not a threat to objectivity.

Hence Heinz Kohut places the self at the center of analysis, and at the center of the self—the need for an empathetic response. Instead of interpretation, he seeks empathetic resonance; instead of disclosure, recognition. The analyst is no longer “the one who knows,” but “the one who feels and carries.” Psychoanalysis ceases to be merely a hermeneutics of symptoms and becomes a phenomenology of encounter.

3. Kohutian Analysis

Kohut would say that the problem is always relational. The client feels separated, unrecognized, misunderstood—in short, invisible.

Like the boy Charlie in the park, panicking when leaving his mother, the client suffers from a sense of existential separation from the world. The remedy is the gaze of a benevolent observer who can heal.

Here, the analyst’s task is to rebuild a bridge between the client and the world—a bridge that does not lead back into fusion, but forward—into a gaze that sees, into a presence that restores life.

This is where Kohutian therapy begins. It does not rely on technique, but on presence and interpretation.

I. Presence

The analyst does not maintain distance or observe from above, but remains in living presence—in contact that initiates transfer. His empathy is not merely understanding, but an act of being with the client, a being that unfolds not in words, but in the silence between words. Presence is not a technique, but a state of consciousness—an openness to the Other without intending to change, fix, or explain them.

In this presence, the client feels that his experience has a place in the world. The analyst’s gaze, tone, breathing, and silence become a new frame of security in which something previously impossible can occur—that someone stays. That they do not leave when pain, anger, or shame arise. That they do not retreat from chaos, but endure it together with the client. Transfer is not created by technique, but by this touch of consciousness—a touch that does not judge or analyze, but witnesses.

II. Interpretations

Interpretations in Kohutian therapy are not objective truths about the unconscious, as in Freud. They do not reveal repressed contents, but reflect the client’s emotional experience. Each interpretation acts as a mirror—it helps the client recognize their own experience through the perspective of the Other.

Interpretations become a bridge between the client’s inner perspectives and the real presence of the Other, enabling integration of experiences and emotional responses. Even incorrect or delayed interpretations can be healing. While not technically accurate, they demonstrate the effort to see, to understand. They reflect the care of the Other.

4. Parallel Identities

Kohutian analysis includes a rich psychoanalytic tradition, but also postmodern philosophy—existentialism, phenomenology, ethics, and hermeneutics. According to these, the relationship is the foundation of psychic life. Outside of relationship, there is only metaphysics of the natural sciences, but they are not alive.

Yet there is room to expand Kohut’s theory: the theory of parallel identities. The idea is that within each of us there is not only one personality, but two, alternating at an extraordinary speed, several times per second. The rapid exchange of “I” and “You” perspectives shapes human consciousness and personality.

Kohut was on the path of this idea. For him, personality is a bridge, a tension arc connecting ambitions and ideals. Ambitions and ideals, or ego and superego, can be seen from the perspective of parallel identities as “I” and “Not-I,” or “I” and “You.”

Psychological problems arise when the exchange of perspectives stops, and the person becomes frozen in one of them – frozen in Me, but without You. Personality is then without a witness—without the Other who can define and mark it. This is where all psychological problems begin. The remedy is always the same: to become visible again, to find someone who sees and understands.

Here I see a continuation of Kohut’s story about Charlie: in addition to discovering the mother and her perspective, Charlie momentarily becomes the mother himself. For a moment, he can let go of himself and view the world through his mother’s eyes. Only then can he see himself from her perspective. In short, growing up means simultaneously being observed and being the observer—able to see and be seen, feel and understand, in the unified experience of “I and You.”

5. Therapy with Parallel Identities

Parallel identities build on Kohut’s ideas of presence and interpretation, but go a step further: the analyst need not remain hidden; on the contrary, he must reveal himself!

Now, the analysis consists of:

I. Analyst Presence

The analyst’s presence in therapy with parallel identities is similar to Kohut’s idea of analysis—stable, predictable, and continuous. The key is not only in words, but in the living presence that initiates transfer.

In this presence, the client feels that someone sees their inner world, even when fear, anger, or sadness arise. Presence is not passive; it is an active act of witnessing and holding space for the client’s inner dynamics.

II. Interpretations

Interpretations complement presence. Their power lies in showing that there is someone thinking and feeling alongside the client, someone who cares. Even incorrect or delayed interpretations confirm that the analyst has their own perspective, that they are human, vulnerable, and imperfect.

Interpretations become a bridge between the client’s inner perspectives and the real presence of the Other, enabling integration of experiences and emotional responses.

III. Gradual Revelation of the Analyst’s Personality

The theory of parallel identities goes beyond presence and interpretation. It emphasizes the gradual revelation of the analyst’s personality. Initially, the client cannot bear the full presence of the Other, but as the relationship progresses, the analyst slowly reveals their thoughts, feelings, and limitations, showing that they are not merely a psychological function, but a real person—vulnerable and human.

This revelation has a dual effect:

- The client sees that the analyst truly exists and can hold their inner world.

- The client discovers that they can momentarily become the analyst—to view the world through the Other’s eyes and thus see himself.

Analysis ceases to be a one-sided transmission of security and insight; it becomes a living, reciprocal play in which the client learns how to be seen, how to see, and how to maintain a relationship—with himself and with the Other.

Conclusion: Returning to Charlie

Charlie’s story gains a new, deeper dimension. We can imagine him sitting in the park—not only as a child receiving his mother’s presence, but as a child who momentarily becomes someone else, able to see the world through his mother’s eyes. In this full presence, Charlie simultaneously sees and is seen, experiencing his reality through the perspective of the Other and thus discovering his own wholeness.

The tension between “I” and “You” is no longer a threat, but a means of understanding and experience. It is a space where parallel identities meet, where the inner observer and inner experience merge in a dynamic dialogue, shaping consciousness and vitality.

This final image connects the entire article: from the first step toward the pigeons, through Kohut’s insights, to the theory of parallel identities and the method of analysis. The reader now clearly sees how the experience of the Other and the gradual revelation of the analyst’s personality allow the client to feel themselves in the world again and to become the analyst of their own inner reality.

Returning to Charlie is not merely a return to childhood—it is a return to presence, the realization that being seen and seeing the Other makes life alive, full, and real. The moment when I and You meet becomes a space in which every inner tension becomes a source of insight.

Literature

Kohut, H. (1984). How does analysis cure? Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ferenczi, S. (1949). Confusion of the tongues between the adults and the child – The language of tenderness and of passion. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis.

Mahler, M. S., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant: Symbiosis and individuation. Basic Books.

Nemet, V. (2025, May 28). New psychoanalysis and parallel identities. https://www.academia.edu/129607071/NEW_PSYCHOANALYSIS_AND_PARALLEL_IDENTITIES

Tolpin, P., & Tolpin, M. (Eds.). (1996). Heinz Kohut: The Chicago Institute Lectures. Routledge.