Antisemitism as an Antidepressant

Depression is usually interpreted as a lack of energy, vitality, or life’s spark. But the ancient Greek concept of thymos—a mix of pride, passion, and righteous anger—gives us a sharper picture: depression is a state without inner fire. A depressed person feels no anger, no power, no sense that they could move the world even an inch. They sit still while life rushes by.

The escape? For many, it’s euphoria, ecstasy, mania. Psychologists call it acting out: short, socially acceptable bursts of energy and rage.

Humans have sought this apparent vitality for millennia. In ancient Greece, Dionysian and Delphic cults used dance, wine, and ecstatic rituals to lift people from despair. Romans added gladiator games in massive arenas, sending thousands of spectators into collective euphoria.

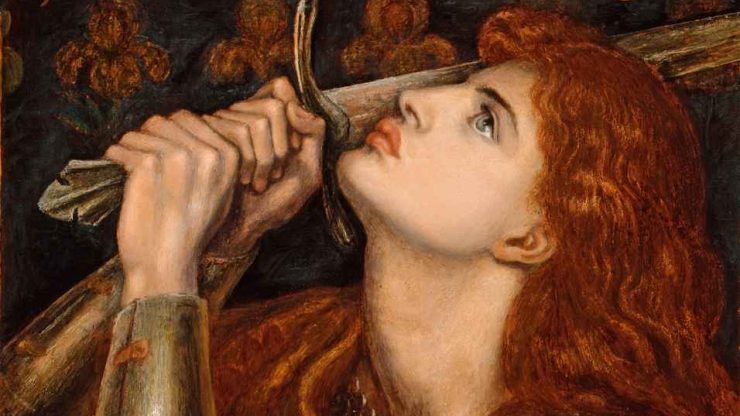

In the Middle Ages, ecstasy took a religious turn. Mystics like Hildegard of Bingen spoke of divine visions, while flagellants sought trance and liberation through pain. Mass dances, carnivals, and folk festivals created collective euphoria, amplified by alcohol and psychoactive substances. Even witch hunts could mobilize thousands, pulling them out of lethargy.

Modern times follow the same pattern. Stadiums, concerts, and festivals spark collective ecstasy. Social media and political rallies trigger digital mania. Rituals evolve, but the human drive for euphoria and belonging remains constant.

Today, the World Football Cup or Olympics act as collective therapy: chanting, shouting, beer-fueled delirium—anger finally emerges.

But not everyone participates. Progressives, intellectuals, the so-called “left” often avoid stadiums. There’s sweat, nationalism, and primitiveness. No sport, no religious ritual, no traditional outlet for venting rage. What remains is a mountain of suppressed anger, buried under layers of intellectual work or self-imposed helplessness.

Of course, the real solution would be to recognize, accept, and release one’s own anger and hatred. To share that anger with the world through language and dialogue. Unfortunately, for most, this path is forbidden. Anger must not be expressed.

The “solution” for some? Antisemitism. It offers an outlet for anger even to those who have denied their own rage all their lives. In today’s political climate, it’s almost the only sanctioned vent: rebellion is forbidden, nationalist chants condemned, but criticism of Israel becomes righteous—therapeutic, even. A protest march turns into a leftist stadium: flags replace jerseys, slogans replace chants, yet the ecstatic release is the same.

Antisemitism becomes a sort of antidepressant. Not because it heals, but because it gives the illusion of power, agency, and belonging to something bigger. Prozac with a megaphone. The only socially sanctioned way to act out inner rage.

Of course, the effect is short-lived. Helplessness returns, the cycle repeats. But as a social phenomenon, it works—for a while. At least until the next World Cup.

Vladimir Nemet