Psychoanalytic Perspective on Embodiment: Anger, Grief and Being Moved

Vladimir Nemet

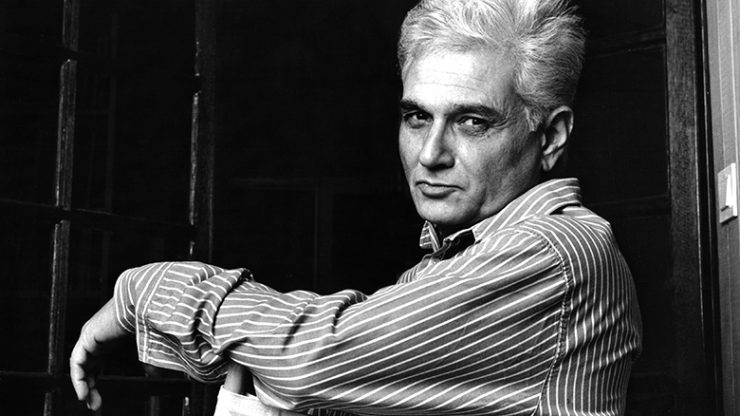

“To have a friend: to keep him. To follow him with your eyes. To see him still when he is no longer there, and to try to know him, to listen to him, or to read him when you know that you will see him no longer — and that is to cry. To have a friend: to look at him, to follow him with your eyes, to admire him in friendship, is to know in a more intense way, already wounded, always insistent, and increasingly unforgettable, that one of the two of us will inevitably see the other die.”

Jacques Derrida

Abstract

Traditional theories of emotion view the affects of sadness and anger as reactions to the same object or event—usually in the context of frustration or loss.

This article offers a new, dialogical perspective: the affect of anger emerges from the loss of my experience of the I, while the affect of grief arises from the loss of Thou.

The rapid alternation of these affects gives rise to the phenomenon of being moved—a vintage of vitality, a sense of living presence and embodied encounter between I and You.

Affects are not mere psychological responses but bodily voices of the psyche—ways in which voids and fractures are transformed into the experience of presence.

The affect of anger transforms and embodies grandiose fantasies of the ideal I, while the affect of grief carries the trace of the ideal Other, Derrida’s “trace of absence.”

They are forces that prevent the disintegration of personality by turning fragmentation into embodied experience—the experience of one’s own body. As usual, we interpret the theory of parallel identities.

Introduction

In classical psychoanalytic and contemporary psychological traditions, affects are often understood through a linear, intrapsychic logic—as reactions toward the same object: frustration, loss, or threat.

Freud, Klein, and Bion interpret affects as complementary yet fundamentally unified responses. However, from a phenomenological perspective, the affects of anger and grief do not respond to the same loss.

The affect of anger arises when the ideal image of one’s Self is disrupted; the affect of grief arises when the presence of Thou is lost.

In the body, this creates an oscillation between presence and absence—a vital experience that testifies to the paradox of I and Thou.

Derrida might say: every affect of grief leaves a trace of the Other—a print of a presence that is physically absent yet existentially and bodily remains.

Freud, Klein, and Bion equate the affects of anger and grief, viewing them as reactions to the same lost object. But such a unified view erases the distinction between the loss of one’s own presence and the loss of the Other.

It is not the same when the ideal image of my Self disintegrates, or when the image of the beloved Other fragments.

Neuropsychological models, although precise in mapping brain activation, often lose the subjective and bodily dimension of experience.

They erase the paradoxical tremor between I and Thou—the moment when vitality witnesses the split, and affect becomes the trace of the Other.

The Affect of Anger: Loss of the Self and the Restoration of Grandiosity

The affect of anger appears when the subject feels the collapse of grandiose fantasies that sustained cohesion. Control and mastery over the world lose their force. Anger then activates the body, awakens consciousness, and calls the subject to reaffirm and reorganize experience into a meaningful whole.

In the body, it manifests as tension, pulse, breath, warmth—sensations that return the sense of “I exist.” Kohut sees anger as a response to narcissistic injury; Winnicott recognizes it as proof of an authentic self; Bion as raw yet creative energy seeking metabolization. Within the theory of parallel identities, the affect of anger does not destroy but illuminates—it marks the boundary of the Self and opens space toward the Thou.

It is the voice of vitality, the embodied “yes” to life: I feel my space in the world.

The Affect of Grief: Loss of the Thou and the Trace of the Ideal Other

The affect of sadness arises when the subject senses the absence of the ideal Other—the figure that had sustained cohesion. Phenomenologically, grief opens the space of silence and of sitting with emptiness. The body becomes a witness to that absence: heaviness in the chest, tears, contraction, slowed breath. In these sensations, Derrida’s trace of the Other remains—the print of the Other still dwelling in the body.

Grief thus becomes a bridge between the imaginary and the embodied, between image and incarnation—a process Kohut calls transmuting internalization.

Rapid Alternation of Affects: The Rhythm of Parallel Identities

The theory of parallel identities describes a subject capable of rapid oscillation between the perspectives of I and Thou. The body vibrates together with consciousness, shifting from grandiosity to vulnerability, from presence to absence. When the subject can endure this rhythm, the phenomenon of being moved arises—the moment when body and spirit breathe together.

Being moved is the simultaneous presence of grief and anger. It marks emotional maturity.

Neurophysiologically, this alternation activates both sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, producing a pulsating sense of presence.

It is the moment when the paradox no longer seeks resolution—it is lived, embodied.

Affects as the Transformation of Fragmentation into Embodiment

Fragmentation is inevitable in the encounter of I and Thou. When Thou appears, I disperses; when I appears, Thou loses coherence. When You are here, I am not.

This is not a defect but a phenomenological necessity of parallel worlds. Affects are what transform this dispersal into bodily experience. The affect of anger strengthens the boundaries of the Self; the affect of grief opens the space for the Thou. Their rapid rhythm—through the phenomenon of being moved—pulses as the life rhythm of presence. Without affects, a person does not truly possess a body—one lives in a world of images.

Affects are the bridge between image and body, between the imaginary and the real; they are the pulse of consciousness and flesh—the rhythm through which fragmentation becomes wholeness.

The Phenomenon of Being Moved: The Affective Apex of Embodiment

The phenomenon of being moved arises in a moment of synchrony—when the loss of I and the loss of Thou occur at the same point in time.

The affect of grief leaves the trace of the Other; the affect of anger reaffirms the boundaries of the Self. The body vibrates between light and shadow, presence and absence, strength and vulnerability. In that vibration, the subject feels vitality—the body becomes a site of encounter; the trace of the Other shines within one’s own presence.

The paradox of I and Thou is not resolved but lived—in the fullness of the embodied moment.

The Advantage of the Dialogical Perspective

The dialogical approach, through the perspective of parallel identities, allows us to:

- Distinguish the causes of affects—the loss of I versus the loss of Thou.

- Grasp the phenomenological sense of vitality and the oscillation between presence and absence.

- Integrate affects without repression—through the body, not through defense.

- Recognize the ethics of encounter—the acknowledgment of the Other and one’s own presence in the same point in time.

- Understand the trace of the Other as a bridge between absence and presence.

Affects are not linear reactions but dialogical, embodied processes. Through them, voids turn into sound, images into pulse, and fragmentation into bodily experience. In the therapeutic encounter, the alternation of anger and grief opens the possibility for the subject to feel both identities simultaneously—I and Thou.

The phenomenon of being moved then becomes the key moment of therapeutic growth: a moment of vitality, integration, and the presence of the Other in both body and spirit.

Conclusion

The affects of anger and grief are not reactions to the same loss. They are two voices in the dialogue between I and Thou: anger responds to the loss of I and restores grandiosity; grief responds to the loss of Thou and leaves the trace of the Other. Their rapid alternation creates the phenomenon of being moved—a moment in which paradox is felt as life itself. Fragmentation is inevitable, but affects enable its transformation. They are the pulse of body and soul, the bridge between image and presence, between world and self.

In this pulsation, the subject finds wholeness—not in calm, but in the vital rhythm of paradox.

Literature

Derrida, J. (1967). Of Grammatology

Kohut, H. (1971). The Analysis of the Self

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from Experience

Buber, M. (1923). I and Thou

Klein, M. (1940). Mourning and Melancholia

Levinas, E. (1961). Totality and Infinity

Stolorow, R. D., & Atwood, G. E. (1992). Contexts of Being

Vladimir Nemet (2025). New Psychoanalysis and Parallel Identities