Vedanta, Schrödinger and Parallel Identities

Vladimir Nemet

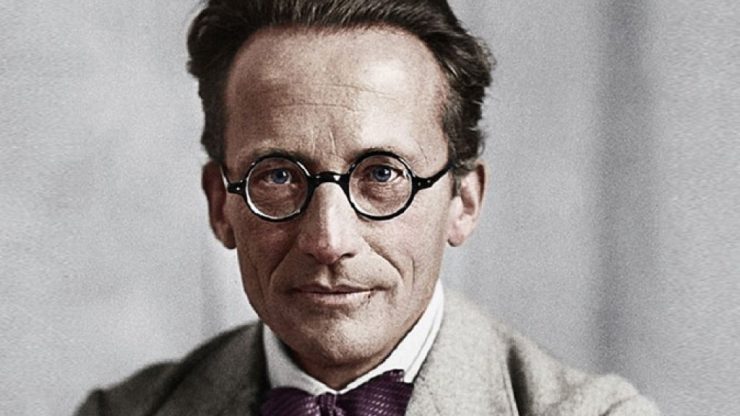

“The state of mind is not something that can be explained by physics; it is a primary fact.”

Erwin Schrödinger, Mind and Matter (1958)

Introduction

One of the deepest paradoxes of life concerns the phenomenon of the nature of consciousness. Although it appears that each individual exists as a separate point, philosophy and contemporary physics suggest otherwise: behind the multitude of subjects lies a single universal consciousness. This chapter explores this idea through three complementary perspectives: Vedanta, Schrödinger’s physics, and the theory of parallel identities.

Vedānta teaches us that consciousness is a unified field from which all diversity of life emerges; all differences among beings and phenomena are illusory, and the world is pervaded by Māyā, the illusion of separateness (Torwesten & Rosset, 1991). Schrödinger, from the perspective of modern physics, confirms that the observer and the observed are not separate; life and identity emerge through interaction with the environment, yet all occurs within a single continuous field of consciousness (Schrödinger, 1944). Finally, the theory of parallel identities reveals how this unity manifests in psychological experience: the sum of Self and Not-Self remains constant—always one, independent of the individual’s perspective or experience.

Understanding the structure and dynamics of consciousness is crucial for psychoanalysis and psychotherapy, because it provides a map of the inner landscape, allowing therapists and patients to navigate the interplay of Self and Not-Self, recognize the patterns that shape experience, and cultivate a deeper, more integrated sense of psychic unity (Kohut, 1959; Buber, 2008; Levinas, 1969).

1. Vedanta: Consciousness as a Unified Field

Vedānta, through centuries of reflection on the nature of existence, unveils the fundamental structure of the world: all that we perceive emerges from a single consciousness. The world, in its apparent diversity, is called Māyā, the illusion that conceals unity. The distinction between subject and object, between Self and Other, is not real; it is phenomenological, a way in which consciousness experiences itself (Heidegger, 2008).

Within this framework, life is not fragmented. Every individual, every being, every point of perception appears as a different perspective of the same universal field. The field of consciousness is immutable, while its manifestation through perceptions and relationships creates the illusion of multiplicity. Identity is not ontologically separate, but a phenomenological form of consciousness playing with itself

Vedānta reveals a subtle truth: there is no consciousness beyond the one. Each individual is not a separate “Self” in an absolute sense; it is a localized manifestation of the singular consciousness that passes through infinite forms and perspectives. Through this lens, life appears as a dynamic maintenance of unity through apparent multiplicity. Māyā, the illusion of separation, does not negate the unity of consciousness; it merely conceals it, inviting discovery through introspective observation and lived experience (Torwesten & Rosset, 1991).

While Vedanta sees Māyā as a concealment of reality, Heidegger’s Aletheia is an unveiling – together they show how illusion and truth coexist in the experience of being (Heidegger, 2008).

2. Schrödinger: Consciousness and the Observer

In modern science, physicist Erwin Schrödinger approaches this philosophical intuition through quantum logic. In his work What Is Life?, he asserts that the observer and the observed are not separate; consciousness does not stand outside the world but shapes it. Living beings sustain life through continuous interaction with their environment, yet they are always manifestations of the same field of consciousness (Schrödinger, 1944).

Schrödinger emphasizes that the unity of consciousness allows stability and continuity of life, despite its complexity and fragmentation into various subjects. Each observing subject is not a separate entity; it is a local point of focused consciousness, through which the total field manifests. His analysis confirms the Vedāntic insight: differences between individuals, between the observer and the observed, are apparent and functional, while ontologically real is one singular field of consciousness.

This perspective bridges philosophy and quantum theory: life arises as a space of interaction, dynamics, and the preservation of conscious unity, where the illusion of multiplicity does not diminish essential unity. Every perception, every subject and object, every biological activity, is a manifestation of one consciousness expressed through myriad forms (Schrödinger, 1944).

Just as Schrödinger in quantum physics emphasizes the inseparability of the observed and the observer, psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut shows that the client’s inner world can only be observed through introspection and empathy – as he writes:

“The inner world cannot be observed by our sensory organs… we can observe it as it unfolds in time: through introspection within ourselves and through empathy in others” (Kohut, 1959) – thus demonstrating how observer and observed coexist in the experience of subjectivity.

3. Parallel Identities: The Sum of Self and Not-Self

The theory of parallel identities, which I develop in my writings, provides a psychological framework for understanding universal consciousness. Each subject consists of two parallel perspectives: Self and Not-Self, which alternate in time. Their interplay produces the phenomena and experiences of life and identity, yet the total consciousness—the sum of both—remains constant and universal.

Why the sum is always one?

- Unity of consciousness

Everything that arises—Self and Not-Self, I and You, subject and object—belongs to the same field of consciousness. The “Self” is the current point of focus, while the “Not-Self” is all else with which the Self relates. Since both are manifestations of the same field, their total sum remains constant—one.

- Parallel dynamics

I and Not-I are not separate systems; they form two sides of the same tension. When the Self dominates, the Not-Self recedes; when the Not-Self takes focus, the Self withdraws. This constant redistribution demonstrates that the sum of both aspects never disappears nor multiplies—consciousness merely shifts between perspectives, while the total field remains unchanged.

- Ontological principle

Sum(I + You) = 1 symbolizes the whole field of consciousness manifesting through diverse perspectives. No being creates additional consciousness or loses it; it only shifts focus between its parallel identities, maintaining the constant flow of universal consciousness.

Trauma as crystallized gaze

Through this framework, life appears as a dance of consciousness with itself, where the distinction between Self and Not-Self is not a loss of unity, but its manifestation. Every perception, interaction, and introspective experience serves to maintain the sum that is always one, while simultaneously creating the impression of diversity and multiple identities (Levinas, 1969; Buber, 2008).

In other words, one universal consciousness exists through all forms of life, and parallel identities demonstrate how this consciousness manifests experientially through alternating perspectives. Each subject, through the dynamics of Self and Not-Self, actively sustains the unity of consciousness, participating in the unbroken flow of the universal field.

Māyā, the illusion of separation, clings to a single gaze—either the Self or the Other—crystallized into a frozen identity by the weight of trauma and deep disappointment. The purpose of psychoanalysis is to rekindle the exchange of perspectives, allowing Māyā to be deconstructed and the fluidity of Self and Other to reemerge (Kohut, 1959).

Conclusion

Through Vedānta, Schrödinger, and the theory of parallel identities, a subtle truth of universal consciousness emerges: differences and fragmentations, the illusions of Self and Not-Self, subject and object, are all manifestations of a single continuous field. Māyā conceals the wholeness of consciousness, Schrödinger affirms its continuity in quantum and biological reality, and parallel identities reveal the psychological dynamics that uphold unity in lived experience.

Life, in its complexity and multiplicity, appears as a dance of consciousness with itself, where the sum of Self and Not-Self remains constantly one. Every perception, every encounter, every introspective realization contributes to maintaining the continuity of universal consciousness, while simultaneously creating the impression of diversity and multiple identities.

In other words, one universal consciousness pervades all forms of life, and through parallel identities, we can experientially apprehend its enduring unity. Each subject, through the interplay of I and You, actively participates in this unbroken flow, revealing in everyday experience the silent yet indestructible current of unity that binds all.

References

- Buber, M. (2008). I and Thou. Howard Books.

- Heidegger, M. (2008). Being and Time. HarperCollins.

- Kohut, H. (1959). Introspection, empathy, and psychoanalysis: An examination of the relationship between mode of observation and theory. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 7(3), 459–483.

- Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Duquesne University Press.

- Schrödinger, E. (1944). What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. Cambridge University Press.

- Torwesten, G., & Rosset, P. (1991). Vedanta: The Science of Self-Realization. Motilal Banarsidass.